The Double Agent’s production platform ensures that BIO is a living design organism responding to the needs of society and the design field. This year, we will develop projects aimed at intertwining diverse media and disciplines such as design, craft, applied arts, and films into processes and results that contribute to the theme and deliver a renewed perspective on design.

Selected participants will address the topics of materiality, language, design as a public tool, marginalised communities and film, together with eight esteemed designers who will lead the groups as mentors until the exhibition presentation.

BIO28 Double Agent mentors are matali crasset, dach&zephir, El Último Grito, Polonca Lovšin and Studio Yukiko in collaboration with Grashina Gabelmann.

Melting Through

Beekeeping is one of Slovenia’s deeply rooted traditions, representing a collaboration between flowers, bees and beekeepers. With five beekeepers per 1,000 inhabitants, Slovenia ranks among the top countries in Europe for the number of beekeepers per capita. Slovenia is one of the few countries that grants legal protection to bees, specifically to the autochthonous Carniolan bee (Apis mellifera carnica). Can something as traditional as beekeeping be paired with a completely new way of perceiving social equity, equality and diversity in our society? Can beekeeping become a double agent?

Melting Through is a platform project developed for BIO28 Double Agent: Do You Speak Flower? by the multidisciplinary artists Katarina Babič Derenda, Mori Sikora, Beti Frim and Ines Sekač under the common name XenoScapers collective, in collaboration with mentor matali crasset. Together they meaningfully intertwined beekeeping, inclusivity and a responsible approach towards material use, and created a welcoming dialogue that echoed throughout Double Agent.

- You’re such a diverse collective, what is your background and field of work?

Katarina Babič Derenda: I graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana, but now I like to read about queer theory and neurodivergent empowerment. I’m a queer and neurodivergent visual artist.

Beti Frim: I earned a bachelor’s degree in graphic design, but right now I’m doing a masters in video and media art at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana. Before this project, I was working as an audiovisual artist for queer performances.

Mori Sikora: I earned my bachelor's degree in Poland from Curatorship and Art Theories, and right now I’m finalising my masters in painting at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana, focusing on textile art, natural printing, and dyeing techniques using foraged flowers, herbs and other plants.

Ines Sekač: I study at the Department of Pedagogy at the Faculty of Arts, Maribor.

- What drew all of you together?

Beti Frim: Definitely our interest in ecology and queerness, and the fact that we see both worlds interconnected. It felt intuitive to form a collective and start working together. I have collaborated with Ines before, and Mori and Katarina worked together before too, but when we saw the BIO28 open call, we decided to develop something completely new together. The fact that we’re all really interested in environmental theory and art projects connected with nature was a good starting point.

Ines Sekač: We found the intersection of art and nature very interesting and important. We wished to address both the sustainability of art practices while also finding a way to address children in an open way. Since my background is in pedagogy, I’d like to emphasise how important it is to address children in a manner that is more open, so they’re able to embrace the love for nature from a young age. This way we can become more empathetic as humans.

- What were your first impressions when you noticed the BIO28 open call, and how did your first encounter with Double Agent go?

Beti Frim: Initially, we took the theme of BIO28 Double Agent: Do You Speak Flower? quite literally. But then, when we researched the secretive language of flowers, we realised that it’s about the critique, the metaphor for women, and it’s in a field of feminism. We started referencing new materialism because we resonate with it, as it includes other species and treats them as equals. They are agents that should have the same rights and recognition as we do. This was a key factor in our work: we perceived the flowers and the bees, as well as all other participants, as equal stakeholders. By doing so, we no longer focus on the flower or the language of flowers, but on the surrounding entities as well.

Mori Sikora: We mainly tried to go beyond viewing the world as a binary one: male and female. We expanded our thinking and tried to invite all species and everyone into our process. We tried to connect this approach with the Beeswax Studio and Grotto, as well as with the mentor and the Double Agent theme. While doing all of this, we tried to invite the beeswax into the process as a complex entity.

Katarina Babič Derenda: We tried to add transgender and queer themes to Double Agent.

- In the project Melting Through, you're emphasising a collaboration between a plant, a bee and a beekeeper. How would you describe your process of work? What were some initial ideas that you thought would fit your project but didn't end up in Melting Through?

Mori Sikora: From the start, as you say, we wanted to connect with the brief of our platform - the bees and their beeswax - with nature and pollinated plants and flowers. Without bees, many flowers and other plants, such as vegetables and fruits, would not exist as they do now. Some species self-pollinate, but the majority still need bees to exist and survive. What we initially considered including, but which did not make it into the final project presented at MAO, were smaller wall installations where people could attach their beeswax forms created during workshops. We created just one large installation instead, that incorporated both the video and the beeswax forms, rather than making separate ones.

Katarina Babič Derenda: Our process was fluid, and the stages in which we were creating were very interchangeable. We kept experimenting with beeswax, and even after these months we can say that we barely got to know this material because it’s such an interesting material to work with. I would describe our process as intuitive, too - it was a project in which we had no idea where we were going to end up. We started by researching biodiversity and the connection of all beings, but then over the months it evolved into a more queer theory-based project.

Ines Sekač: One of the problems we faced during the process of developing the project was the question of whether we were perhaps over colonising the bees. Or if we were misusing and overusing the wax. This would have applied if we’d gone into mass production or into a design project with something tangible as an end result. Melting Through is not meant to be capitalised, it’s meant to be a medium for something completely different: the experience. We consciously sacrificed the amount of beeswax for this tactile workshop in order to raise social awareness about our togetherness. By doing so, this beautiful smelling material brought us together throughout our process.

- That’s an interesting perspective - how did you source your beeswax, then?

Beti Frim: While the beeswax for the workshop was bought at a local company, Samson Kamnik, we also did a lot of research on what would be the right way to use it. My grandfather is a beekeeper, and he mentioned that the beeswax for candles actually comes from discarded hives and is low quality wax. For example, if a beekeeper stops taking care of a colony and the colony dies, the wax stays in the hive until a new colony is introduced to the old hive. But if the colony dies due to a disease, the wax has to be discarded from the hive because it’s contaminated. In Slovenia, no beekeeper just sells wax away to companies who might make something out of it. When it is sold or given away for candles, it’s because it can no longer be re-used by the bees. For this kind of project, it made sense to use beeswax and it turned out that it really conveyed the meaning of our work very well. If we had unlimited time, of course we’d source discarded wax from local beekeepers and make our project only from that type of wax, but we had to be resourceful and collaborate with local wax traders.

- With your interesting approach and knowledge, you created a portal into the theme, opening up even more inclusive ways of perceiving Double Agent, or even our world.

Katarina Babič Derenda: Absolutely, I agree.

Beti Frim: Also the workshops did that, they added another dimension to our concept because participants became co-creators of the hive that you can see in MAO. It would look completely different if we’d not had workshops, but in the end they played a big role in our approach. Collaboration and the relationship with the participant is a process, and also a very intuitive one. You have to let go of any expectations and melt yourself with the process which is out of your hands.

- With the workshops, you're also Double Agent-ing and creating a safe space to discuss queerness, neurodivergence, disabilities, human and non-human entities, etc. You're raising awareness about social equity through inclusivity and giving a platform to a more horizontal approach towards learning and participating. Would you be able to share more about it?

Katarina Babič Derenda: We wanted to give the platform to queer people - and I’d like to emphasise the importance of the community interactions that Beti mentioned, such as the one that we had at TransAkcija. TransAkcija had its first ever Trans-con, and it was a really beautiful community gathering, it was incredible. Lots of queer individuals participated in creating these shapes out of beeswax - we created a web of connections, and there were a lot of joyful moments of trans and neurodivergent solidarity. At that workshop, we accomplished what we set out to do with this project because people seem to enjoy crafting with their hands and playfully engaging with these themes.

- How did you design your events so that a safe and open atmosphere was created where people felt comfortable and welcome?

Katarina Babič Derenda: We worked closely with TransAkcija, who organise trans events, and they helped out a lot with Trans-con. We were always transparent in our language regarding who these events are for: queer and neurodivergent people, first and foremost. Whoever showed up, showed up; and it ended up as a lovely experience.

Beti Frim: What helped a lot is that we know this community really well. Trust played a key role in co-creating it, but there was also a lot of spontaneity. Our team took the time to discuss our workshop with each individual. Of course we put out an intro online beforehand - some decided to read it, and some didn’t. And our team also decided not to have a formal introduction. We deconstructed the notion of what a workshop should look like. And once the participants got past the idea that this was just about cool shapes and colouring the wax, they realised that they were part of something bigger.

Ines Sekač: It’s important to emphasise that we organise two types of workshops, and the ones in MAO were done a bit differently than Trans-con because we wish to adapt to different age groups and audiences. With children, we used neutral language and we emphasised the equality of nature, humans and non-humans. We steered away from the non-binary aspect or the gender problematic and the binarity of it. However, if we noticed that older participants were interested in these topics, we decided to have an open conversation. With children, it was more about sharing equality and togetherness in the context of the exhibition.

Participants of Trans-con experimenting with beeswax pouring. Photo: Urša Rahne.

- What was the feedback from the participants?

Beti Frim: Actually, a lot of people returned for another round of workshops. The participants were from all age groups, and I’d like to emphasise that the smell of beeswax created a warm and inviting atmosphere too. When the participants figured out how the pouring worked, they all instantly became designers themselves; they had to be creative about how to attach their work to the wall, and it was totally design thinking. By adding natural colours, they were optimising their form and they had a choice: either take it home or add it to the wall. In this way, Melting Through was also a design project.

- And how did your relationship with your mentor matali crasset evolve?

Beti Frim: matali also introduced beeswax as a material that can offer alternative ways of designing, but we preferred to view it as an entity or a form that can translate different meanings and connections. Her workshop space is made for making useful objects out of wax to explore the potential of this material as a design material, and what we added is a perception that it can also be an art medium. By doing so, Melting Through and matali’s installation are coexisting together.

Ines Sekač: Not only coexisting, but both projects are communicating with each other.

Installation Melting Through at the BIO28 Double Agent: Do You Speak Flower? exhibition. The installation and a participatory project features a video composed of footage of bees, flowers and nature, combined with 3D scans of beeswax pieces. This video is projected onto a wooden panel framed with beeswax. Photo: Lucija Rosc

- We’re plagued with extraction-based materials and we’re existing in late stage capitalism: there’s lots of oil, lots of mines, which contribute greatly to social inequity. As designers, you decided to emphasise a material that is not based on extracting from nature but is based on a relationship between species. How do we weave back responsibility into our practices?

Mori Sikora: Beeswax is an intriguing material to work with. Of course it has its limitations, but it is usable and can have other potentialities than soy wax or paraffin. Designers today should be creating and finding ways to use the materials that are already around us. What if we would simply start re-creating existing pieces with different, better, more environmentally conscious materials? Or simply mending the existing, like the kintsugi method - the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery. What if we create leather from mycelium, or from cellulose or even from kombucha, which can be made from fermented tea? We’re still researching how sustainability and circularity can be applied to the world we’re living in now. Nowadays we have more knowledge, but it doesn't seem that we’re applying it at all. We’re surrounded by so much unnecessary plastic!

- You even reinforced this stance by incorporating natural dyes and powders, using only natural pigments and elements. In doing so, you also educated participants about the richness of our environment without depleting it.

Mori Sikora: Yes, we combined beeswax with natural pigments from Poland, such as beetroot, black carrot and spirulina. We incorporated pigments from natural soil found in the Netherlands and Great Britain, along with various dried clays ground into colourful pigments. We also introduced dried flowers, like hibiscus, lavender and rose petals, which were later added to the beeswax installation and then by participants during the workshops.

- In a way, your project could even be slightly anti-design because it offers a different look on the production platform, on BIO itself, and even on design. We need to stop collectively expecting an end-product out of a design project. You offered a fresh perspective about what else design can bring, and emphasised the process itself.

Katarina Babič Derenda: Exactly, and what’s also important is that not all of us from this collective are designers. Actually, only Beti is a designer by profession, the rest of us are artists. It’s important that each of us has a different set of skills and perspectives, and actually that’s exactly what practices need to do: reach out to one another and collaborate. I’d like to borrow Timothy Morton’s quote, which says that science is too important to be left only to scientists. And this quote really emphasises our approach as well.

Mori Sikora: Melting Through is really about collectivism, about togetherness - when creating, we’re not creating a final object, but the process itself.

- Because you’re coming from different practices you can analyse the profession of design from a different standpoint - how do you see the role of design today, and what changes do you anticipate?

Mori Sikora: Everything is designed, either by nature or by humans, but the question is about the necessity. Just because we can, do we need to? Nowadays, we're over-producing just because we can, without ever asking ourselves the questions: who will use it, does it have a purpose, or a meaning? But design should have the purpose of rethinking. We’re past the time where we used to create for the sake of creating. Now we’re facing the consequences of this approach. With art, you feel and put the feeling into art, but with design, we should emphasise the process instead of a product, and think about the longevity of the project: how can it be used again and again. The world we’re living in today is collapsing, but nature will still grow back again.

- In your work, you're deconstructing old inherited thinking patterns as well as societal expectations and oppressive systems. Which one is the most important to deconstruct collectively within our lifetime in order to have a more inclusive society?

Katarina Babič Derenda: Systemic oppression - it’s so broad, extensive and deeply rooted that it’s a really difficult one to get rid of. But at the same time, it’s hard to pinpoint and focus on just one, because all oppressive systems are interconnected.

Mori Sikora: I agree with Katarina, and I’d add the systems that are based on self-interest and self-profit. Greed is disabling us from collaborating, from focussing on love, acceptance and respect.

- If you could pinpoint one or several messages from your installation, what is the main takeaway you hope participants will leave with?

Katarina Babič Derenda: It would be to foster empathy.

Ines Sekač: Embrace tactility! Our participants get to experience that they are very much capable of making something by themselves. Nowadays, everything is pre-made, pre-cut, shaped into a mould, and we’ve lost the joy of creating with our hands. Design can be dispersed and unique to each user, and you can experience making your own sculpture, candle, creative object that can at the same time fuel your love of nature.

The interview was prepared by Nuša Zupanc Pavlič, Editor of BIO.

*****

The Beeswax Studio and Grotto is a platform led by matali crasset. matali crasset has championed design at the crossroads of artistic, anthropological and social practice. She is working towards creative, living and everyday design and asking herself how can design contribute to living together and support us in the contemporary world?

After creating one of the most successful spatial installations Common stove for 25th edition of the biennial Faraway So Close, the participation of the local community echoes into this production platform.

This production platform revisits an ancestral practice in a different way, so as to reinvest our sensibility and allow us to reconfigure ourselves. Beekeeping, which is a Slovenian way of life and a major activity in the country, can help to establish a process that is more respectful and less destructive to our ecosystem. Building on this foundation, and using honey-producing flowers as a starting point, Beeswax Studio and Grotto proposes to focus not on honey, but on beeswax. This natural substance says a lot about our contemporary world: it has to stand up to stiff competition from industrial waxes made from soya (the bean), palm oil and paraffin (via petroleum). Beeswax is obviously the most natural, and it transcends the dividing lines between the plant and animal worlds, raising questions about our own place within the living world. So what remains to be explored is the place, if any, that human beings might occupy within it.

The Beeswax Studio and Grotto platform will consist of a wax workshop that will host research focused on beeswax, exploring natural dyeing using local plants and minerals, the creation of low-cost molds, and the manufacturing of modeling wax, as well as waterproofing textiles and wood. During the upcoming BIO28, a series of public workshops will take place where participants will engage in collaborative experimentation with wax.

(un)woven tales

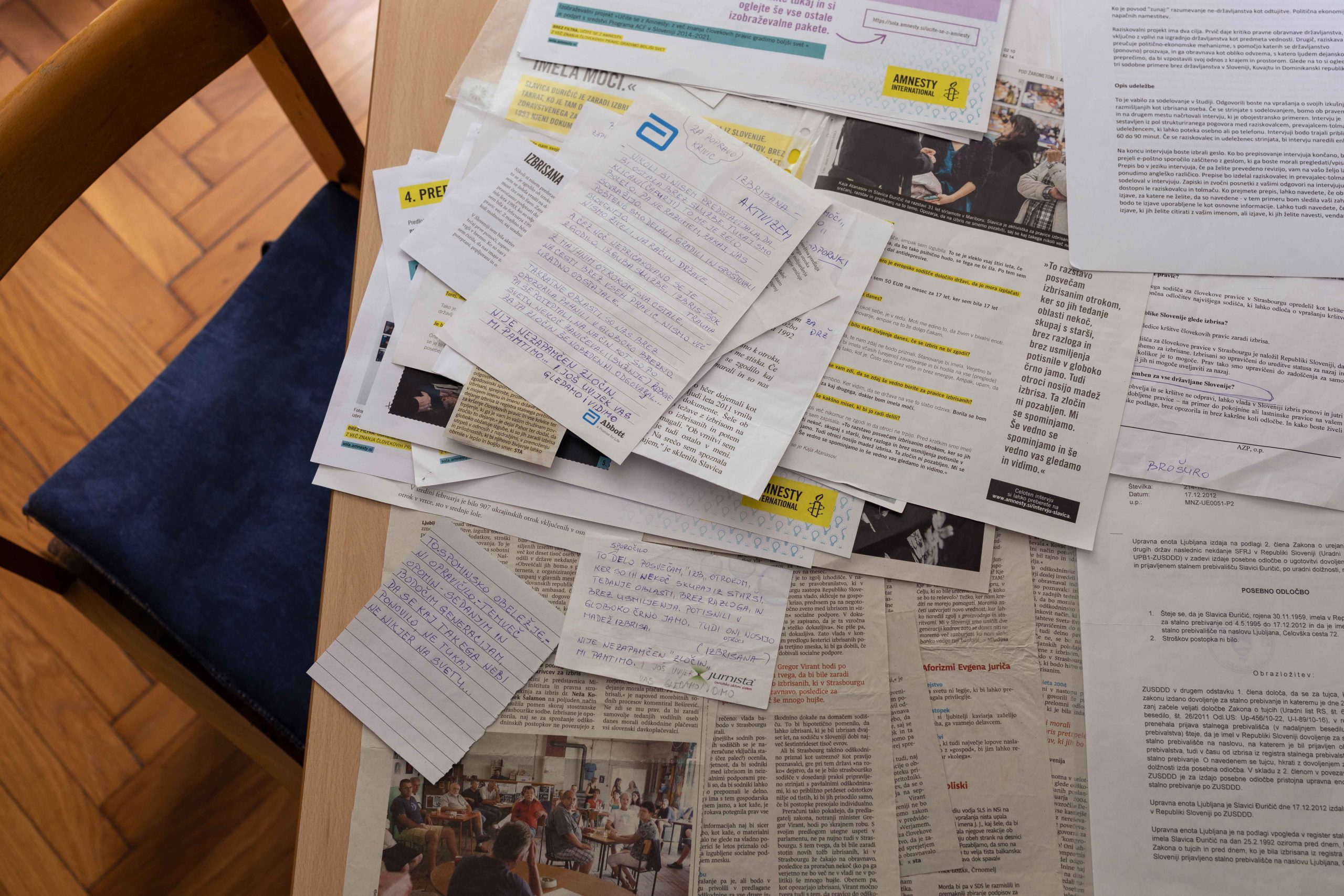

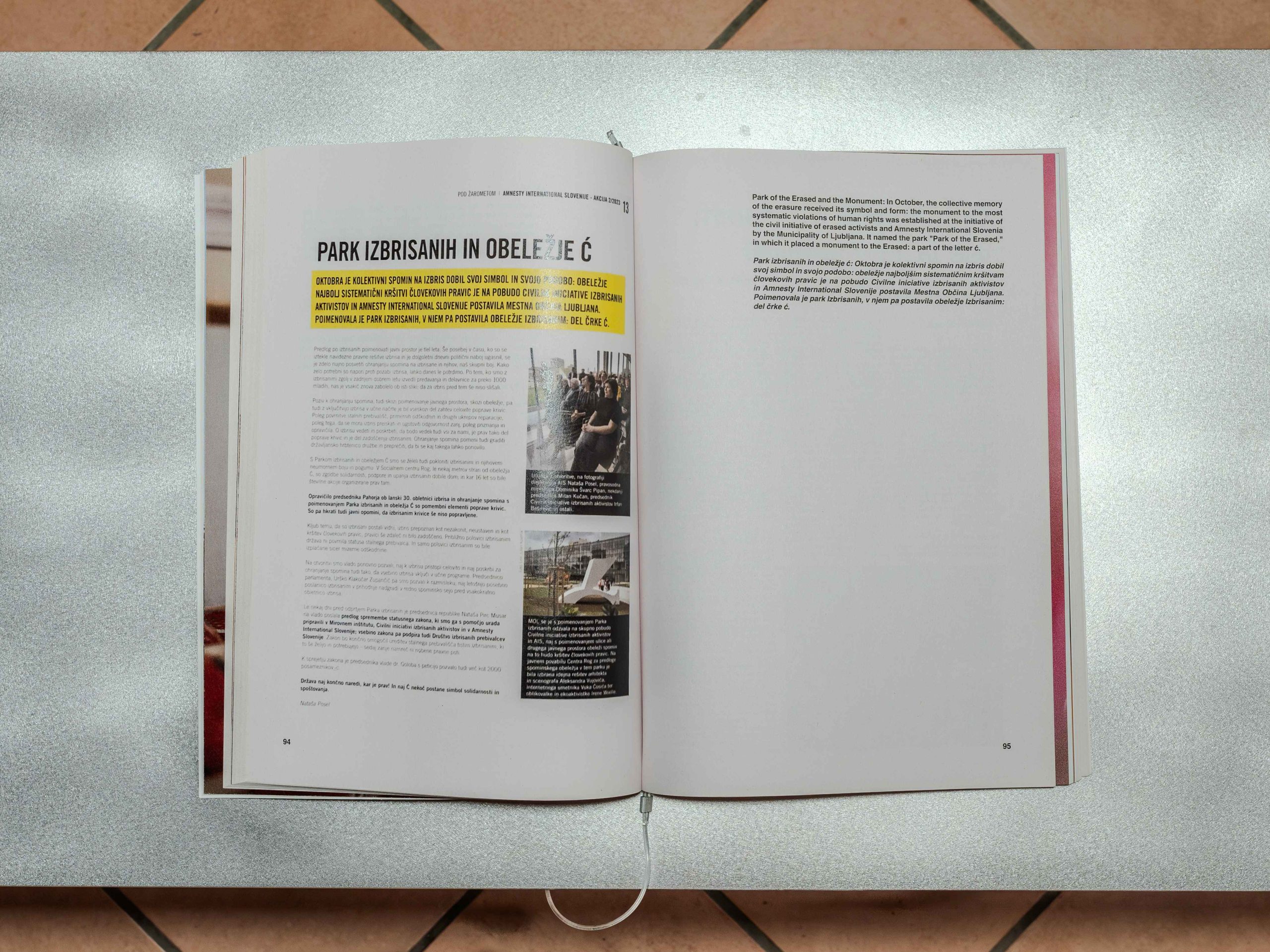

Not Erased is one of the production platform’s projects developed for BIO28 Double Agent: Do You Speak Flower? that aims to amplify the voices of the Slovenian erased people. On 26 February 1992, after the breakup of Yugoslavia, at least 25,671 individuals, 5,630 of them children, were unlawfully erased from the Slovenian registry of permanent residents, and their records were transferred to the registry of foreigners. None of the erased were notified about this, nor were they aware of the grave consequences it would have.

As a result, they were stripped of their legal status and basic human rights. Imagine navigating life without access to medical care, being unable to rent an apartment, work, or send your children to school - to name just a few of the struggles that Slavica Đuričić, Vladica Ilić and Irfan Beširević endured and were willing to share for the (un)woven tales.

The mentors of the Not Erased production platform, Florian Dach and Dimitri Zephir from the Parisian-Guadeloupean studio dach&zephir, prefer to be called researchers rather than designers. Their approach relies on acknowledging both the marginalised stories and the history of a specific place, and translating these processes into the final outcome. This approach merged with the diverse expertise of Anna Odulińska and Nika van Berkel, a Polish and Slovenian-Dutch duo based in the Netherlands. Together with mentors dach&zephir, Anna and Nika developed the project (un)woven tales, through which they intertwined design, craft, and awareness-raising, in a meaningful and visually compelling way

Anna and Nika visited homes of Vladica and Slavica, where they filmed the interviews.

- Your background is in architecture, but for this project you dived into design. How did you start working together, and what were your thoughts when you first encountered Alexandra Midal’s vision for the Double Agent?

Nika van Berkel: Anna and I met at an architecture office in Rotterdam, where I still work, though Anna moved onto other ventures. In the office, I collaborate mostly on housing and school projects, where my expertise lies in soft transitions between inside and outside spaces and the public realm surrounding the buildings. I work four days per week, and this and this one extra day away from my main job allows me to focus on my other practice in which I am particularly interested in blending disciplines in unexpected ways and exploring the intersections of architecture, landscape, sound and art, testing their boundaries and how they influence one another.

Anna Odulińska: We always wanted to create something by combining Nika’s passion for space and sound with my focus on photography and video. When Nika shared the BIO28 Open Call with me, I was immediately into it. We also quickly chose the Not Erased platform because it aligned perfectly with the media we’re interested in. I currently work as an architect in a big international firm, and as an architectural photographer, specialising in interior photography and documentation. When I work as a photographer, I also work and think as an architect: for me, it’s all about the complexity of the profession. Usually, I’m trying to focus on the story of the project. It's easier for me to dive into the project when it has a complex story behind it, so that I can organise and reduce the subject to its essence through research and visuals. Exactly the same motif that drives me in architecture appeared with the Not Erased project: storytelling.

Nika van Berkel: We work well together because we share the same values and we’re both interested in combining different practices together.

Anna Odulińska: And with the BIO28, all of the disciplines we worked in before came together. Our architectural approach really reflects in the design thinking and storytelling of (un)woven tales. Nika’s passion for space and sound and mine for photography, image and stories came together, and shaped a great conceptual reply to the Double Agent.

- How did your relationship with mentors dach&zephir evolve through 7 months of work?

Nika van Berkel: They helped us a lot with suggestions about how to include the bobbin lace, which ended up very poetic, while still giving us a lot of freedom when we decided to tell the story with the installation, video and the book. Sharing their knowledge and artistic references was very valuable. It helped us to shape our installation into a powerful yet poetic narrative, honouring the journeys that Slavica, Vladica and Irfan had to make in their search for justice and recognition.

Anna Odulińska: They were perfect mentors in terms of giving us creative space and freedom. From the beginning, we already had a strong idea of what we wanted, and they did what I think good mentors do: they were asking us the right questions. They were shaping our decisions by posing these questions and by sharing several references. Dimitri and Florian introduced us to the emotional meaning behind the objects: how to give form to the emotion or feeling, to represent something immaterial.

- When dealing with such a heavy theme of citizens losing all of their rights. how do you pick which story to highlight? Did you talk to several of the erased individuals?

Nika van Berkel: Actually, no. My close friend worked for the Red Cross and she gave me the contact of Slavica Đuričić. Slavica introduced us to Vladica Ilić and Irfan Beširević, and they were all willing to collaborate with us. Unfortunately, the erased community is getting smaller because they’re getting older and they’re losing the members.

- What did you sense in their stories? How would you describe the way that they coped with their struggles?

Nika van Berkel: What hurts the most is that they had to hide and were forced into invisibility as if they’re worth nothing. For them, remembering these stories is crucial to ensuring it never happens again. That’s why this installation is important. We didn’t just focus on what happened to the interviewees, but also to their families which were affected. Slavica mentioned that there are still people from the erased community who don’t have documents.

Anna Odulińska: During our interviews I was behind the camera not understanding a word, because I don't speak Slovenian, but it made me more aware of the other visual aspects, gestures, and general body language. Listening to the stories of Slavica, Vladica and Irfan we could sense the feelings of sadness, and I would say a lot of helplessness and powerlessness. Back then, there was probably a lot of anger about the situation. Another strong notion was confusion - there was no real help, no guidance on how to navigate such a tragic condition as losing one’s identity. Together with our mentors, we came up with the idea to capture these emotions in the laces. Each piece reflects patterns of the journey they were forced to take - going from door to door, from ministries to governments, from country to country, desperately seeking help that never came.

Stills from the interviews with the erased community. Photo: Anna Odulińska, Nika van Berkel

- What was the moment when you knew that you'd be focusing on Slavica Đuričić, Vladica Ilić and Irfan Beširević's paths and translating their journeys into Slovene bobbin lace? Were there other ideas, concepts and narratives that you thought were worth pursuing but ended up not doing so? Would you be willing to share them?

Nika van Berkel: From the start, we envisioned a video installation. As we delved deeper into Slovenian national motifs and objects, we aimed on telling the story through items found in the homes of the erased. Every home reflects the story of the individual or family living there. But after the first interview with Slavica, we realised that we need to go into a completely different direction: the project had to be about the people and their stories.

Anna Odulińska: We knew that bobbin lace would be part of the project - but how do you translate the story into the motif? When dealing with the challenge of portraying loss of identity or even confused national identity, you have to be careful which motif you choose. First, we focused on the Linden tree and the greenery because we thought that traditional Idrija bobbin lace was too saturated with the flower patterns, and simply not right for this particular project’s theme. We even thought about the Ljubljanica river, but then we decided to incorporate the places, the paths of the erased into the actual lace. But then, as Nika mentioned, we focused more and more on the story, and decided to steer away from viewing the project as a design project but rather as a project that amplifies the voice of the erased. This is how their journeys became prominent.

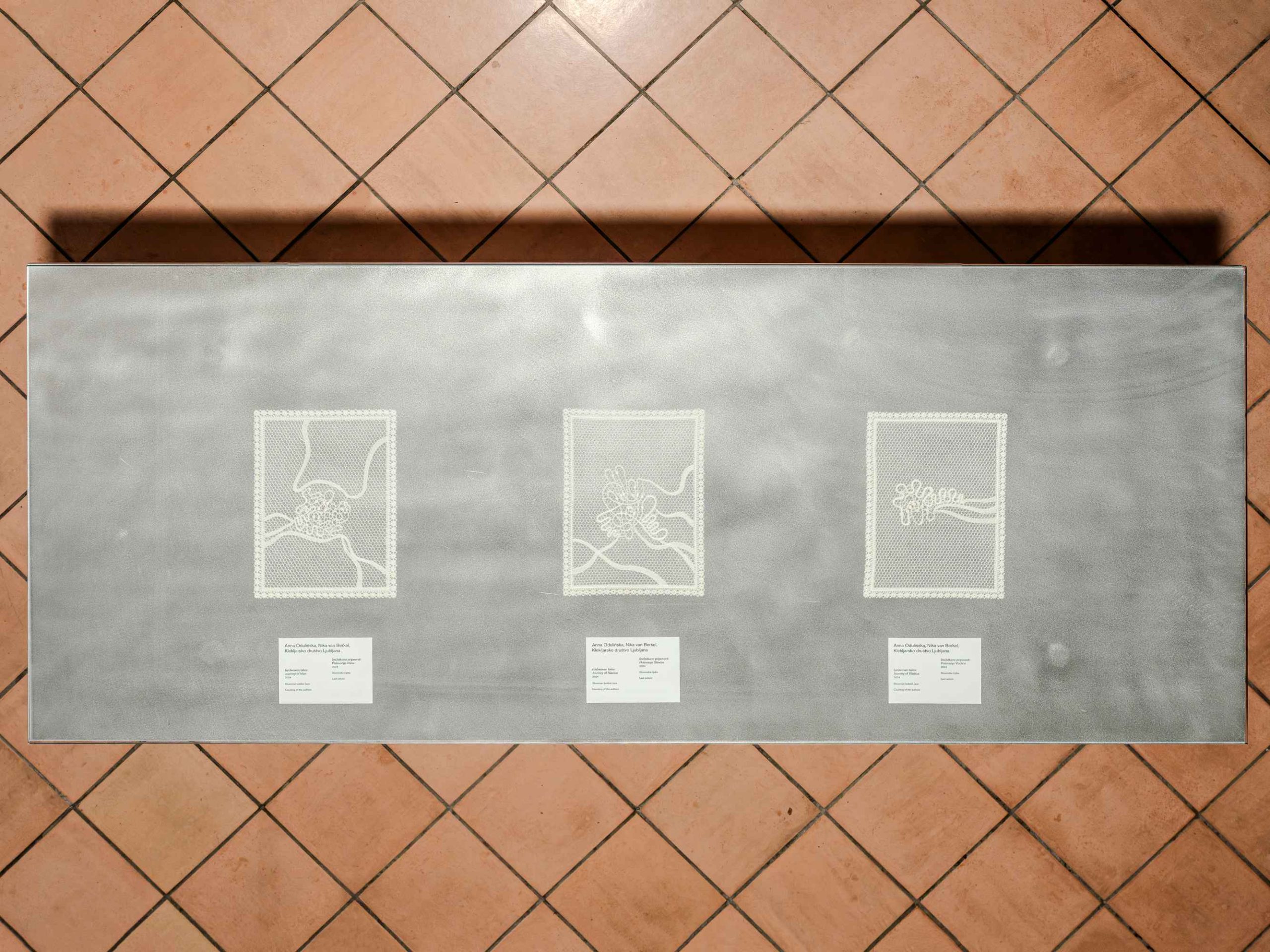

Caption: Journey of Vladica, mapped, translated to a bobbin lace pattern and executed by Bobbin Lace Association. Image 1, 2: Anna Odulińska and Nika van Berkel, Image 3: Bobbin lace Association, Image 4 Lucija Rosc

- In your case, you successfully merged several disciplines together. Where do you see the future of design?

Nika van Berkel: The most fascinating ideas happen at the intersection of several disciplines. There is still so much to explore about what happens when disciplines collaborate: how they influence, challenge and expand each other’s boundaries. The future of design lies in these interdisciplinary dialogues, where architecture, art, sound, technology, social engagement and sustainability come together to create new ways of thinking, experiencing, and interacting with the world.

Anna Odulińska: The future lies in collaboration. It’s no longer about the form, but about the social, sustainable impact the project can bring. It doesn’t have to be clear where the design aspect of the project starts or ends, because it can cross disciplines - and by doing so, it creates a message. Yesterday, for instance, I was photographing a school in a very neglected neighbourhood. It had very tiny spatial interventions, but these small changes had a huge effect on the neighbourhood, introducing new public spaces, opening it for local activities, and making it safer for kids. I’m using this as an example to say that small movements can make a big social change. As architects, we’re often driven by our egos or an ambition to build something, and if I translate this to design I would say that it’s way too much emphasis on the form, sometimes forgetting about the impact we can have. And even collectively, we’re so overloaded with information when instead we should be learning how to listen to each other’s stories and learning to communicate with each other. I guess this project was a great learning experience for me and Nika.

Caption: ‘We realised that they lost everything, papers, … Sometimes the only thing that they had left were some family photos or a family heirloom.’ - Anna Odulińska. Photo: Lucija Rosc for MAO

- The public is generally surprised that this BIO is so different. How did you understand the curatorial approach by Alexandra Midal, and how did you translate it into your project?

Anna Odulińska: Nowadays, you have to be smart and catch attention with colours and forms to attract the visitor. We were, for example, worried about the length of the video, because our attention span is becoming shorter and shorter. But for this video, you have to sit down to watch it. Even though we recorded around 4 hours during the interviews, we decided that we couldn’t shorten it to less than 15 minutes. We don’t want to shorten such an important story, and we’d like the visitor to sit down and watch it in its entirety.

Nika van Berkel: Visitors really appreciated that BIO28 has a more artistic approach - it’s different from past BIOs. What intrigued me was the theme of the flower and its cryptic message. Somehow, this theme resurfaced in our installation, (un)woven tales, even though we didn’t intentionally incorporate it. The bobbin lace pieces, created from the journeys of Slavica, Vladica and Irfan, took on abstract, floral-like patterns. Even in the video, flowers appear, weaving their presence into the narrative...

Spatial installation of the (un)woven tales. Anna Odulińska and Nika van Berkel captured the stories of Slavica, Vladica and Irfan into a film with the help of editor Anna Dobrowodzka, and sound designer Jaka Nežmah. Photo: Lucija Rosc for MAO

Anna and Nika worked closely with the Bobbin lace association Ljubljana that helped to translate the (un)woven tales into Slovene bobbin lace. From left to right: Journey of Slavica, Journey of Vladica and Journey of Irfan. Photo: Lucija Rosc for MAO

- As the authors of the project, you chose to highlight social injustice and give voice and a platform to Slavica, Vladica and Irfan. This is more and more important in the day and age in which we coexist. Do you have any comments on the situation we're collectively in?

Nika van Berkel: Irfan said in the interview that they were on the street all the time protesting and fighting for their rights, wherever and however they could. He said that it’s important to fight for your rights, because nobody else will do it for you. For me, this was the strongest standpoint.

Anna Odulińska: It’s worth emphasising and mentioning the past just so that it doesn’t happen again.

- What is the main message that you’d like the visitor to take home with them?

Nika van Berkel: The main aim of our project is to raise awareness. While living and growing up in Slovenia, I knew about the erased community, but very little about their struggles. Slavica, who travels around Europe to share her story, pointed out that similar erasure occurred in other parts of Europe. Throughout developing this project, we met many incredible people who are actively fighting for the rights of the erased. The knowledge that the erased community holds is incredibly valuable, and it is crucial that they share their stories and educate others about what happened.

Interview by: Nuša Zupanc Pavlič, Editor of BIO.

*****

The Not Erased project will be led by mentors dach&zephir. Graduates of the National School of Decorative Arts of Paris, Dimitri Zephir and Florian Dach founded their creative studio dach&zephir in 2016. Mixing fervor and poetry, their projects echo the thinking of Martinican poet Édouard Glissant and celebrate the urgent and necessary diversity of the world. For the duo, stories and history are starting points in design, acknowledging that objects are mediums for our minds. They believe in the statement that we can’t move forward without acknowledging the past and history.

The production platform Not Erased is a continuation of the studio's reflections on marginalised, minorityized, or erased histories in national narratives and the ways in which they can be reactivated in a contemporary creative dynamic. Conceived as a research and creation unit on the subject of Slovenia's erased people - a group of communities from the former Yugoslavia residing in the country without citizenship rights because they have been erased from Slovene administrative files - the participants will be invited to reflect on the potential manifestations, reactivations, and/or reinscriptions of these individuals and their histories in a national narrative. The aim of the platform will be to form different narratives or backdrops for the creation of one or more works in lace.

How do you tell the story of a lifetime of fractures and struggles in the creation of a motif? How do you represent the loss and erasure of a nationality? What can these other identities – in terms of their cultures and imaginations – bring to the creation of a motif? In other words, what are the modalities of lacemaking and its motif? Bobbin lacemaking – an ancestral skill in Slovenia and a Unesco intangible cultural heritage site – becomes the setting for these fragile stories and identities. Using this know-how, which is rooted in the country's culture and imagination, the aim is to reflect on how the stories of the erased are inscribed in the collective imagination, and possibly on new ways of creating motifs. The various trades will form multi-disciplinary work teams coordinated by a lace-maker.

We invite a collective who will develop a project under the mentorship of Roberto Feo and Rosario Hurtado from the collective El Último Grito. Roberto Feo is Professor of Practice at Goldsmiths, University of London, while Rosario Hurtado co-directs the MA Space and Communication at HEAD – Genève. Their practice responds to an ongoing investigation into the nature and representation of systems.

The aim of this production platform is to create a short film about floriography and the themes of the Double Agent biennial that will simultaneously replace the exhibition catalogue. The film will act as a remnant of the event, a collection of intertwined actions, moments, sights, triggers, and keepsakes inspired by elements from the curatorial texts as well as selected works and the biennial site itself. The film will premiere in Ljubljana, London, Geneva, and Paris. Eventually, the film will be streamed online.

Stories do not have a beginning or an end… not really… they seem to start somewhere and end somewhere else… but not really…. Stories have a protagonist… but not really… stories are just mere adulterated perspectives, a result of “mythification”, an essential simplification required to comprehend reality.

Alpha 60 explains, in its guttural computerised voice, that “reality is far too complex for oral transmission”, so we must create myths/stories that simplify its content for us to understand. The Goddard mastermind imparting some ‘Borgesian’ wisdom.

This story is no different. It does not really start here and will, actually, never end… it’s just a moment in time narrated from a singular perspective… which will eventually stop being interesting or relevant for a narrator to tell or an audience to listen to.

- El Último Grito, 2024

Murmuring Orchids

Prostorož is a non-profit urban design studio that started its journey as an association in 2004 with installations in the old town centre of Ljubljana, and then quickly grew into a studio whose work focuses on the intersection of public space and social equity. The multidisciplinary team consists of architects Vesna Skubic, Maša Cvetko and Alenka Korenjak, communicologist and sociologist Zala Velkavrh and psychologist Naja Kikelj Širok. They approached the BIO28 production platform Movement for Public Speech as double agents, and reinterpreted the cue Do You Speak Flower? in a way that shed light on a social problem and brought to our attention the often unheard stories of women whose lives are dictated by the consequences of the housing crisis. While developing Murmuring Orchids, they collaborated with production platform mentor Polonca Lovšin, a visual artist and architect whose work in public spaces explores innovative ways of inhabiting contemporary society.

Prostorož collective in their studio. Photo: Klemen Ilovar

- What did your first encounter with Double Agent look like?

Prostorož: During one of her first curatorial visits to Ljubljana, still deeply immersed in mapping our city's happenings, Alexandra Midal also managed to meet with us. Our conversation meandered from world affairs to politics and back to our own projects. Along the way, we discovered that we share the same sense of humour, which proved to be a wonderful starting point for our collaboration.

- Having been involved from the very beginning, while the curatorial narrative was still taking shape, how did you experience the process of Double Agent developing and, ultimately, witnessing Alexandra Midal’s curatorial approach coming to life through the exhibition?

Prostorož: The possibility that things, objects and plants may not be what they seem was intensely intriguing to us, and it has been so since our first meeting with Alexandra. We tried to address this duality in all our iterations of the project, and there were quite a few. We were questioning what the flowers on balconies may mean, why there are no potted plants in Airbnb’s, and about 5G towers grotesquely disguised as trees across the Slovenian landscape. We really wanted to address a pressing social issue with this art project, too. Lately, this has been a housing crisis that manifests itself in a lack of affordable flats, expensive rents, a rise in short-term rentals, and poor living conditions. It’s having a major impact on the quality of life in cities. Since Alexandra wished for us to focus on the experience of women, we chose the orchid as our double agent, as a plant that represents a characteristic, ever-present element of the living environment in which a woman lives in contemporary Slovenian society.

- Since you’ve already shared a bit of your process, how would you describe the importance of it and all the research about the local environment that you did during the seven months of developing Murmuring Orchids?

Prostorož: We had so many ideas and iterations of the project, that the work process was as interesting as the outcome itself. On the other hand, it was quite frustrating to conceptualise this project due to the fact that BIO is a living design organism with several stakeholders involved: the curator, the coordinating team, the mentor Polonca Lovšin, the theme of the biennial… Nevertheless, Polonca’s input added another dimension to our work. As an artist, she was guiding us through the process of navigating the tiny production budget and translating our concept into a compelling experience for the visitors. We also had an internal goal to connect the project to local initiatives and activities. We managed to do so with the iniciativa Stanovanjski blok (Block of Flats initiative). Alongside developing an art project, we tried to produce meaningful materials that could be used by the activists, too: recorded stories of women that are played as the soundtrack of the installation were broadcasted on one of the protests. We’re also hopeful that the installation at MAO might be insightful for audience who is not affected by the housing crisis at all.

’We had so many ideas and iterations of the project, so the work process was equally as interesting as the outcome itself.’’ - Prostorož. Photo: Prostorož.

- Could we say that your collaboration with Polonca Lovšin wasn’t a typical mentor-mentee relationship, but rather a more horizontal one, based on complementing each other’s ideas, and collective thinking around a specific theme?

Prostorož: We seldom have the opportunity to work with a mentor so we were happy to work with Polonca. She opened up certain issues that we typically don’t encounter in our everyday practice. We had some great discussions, and she was so interested in our work that she was with us the whole time. The production process was in no no way linear, though, because we took the liberty of interpreting Alexandra’s brief in a very vague way. We didn’t want to take it too literally but rather use this opportunity to create as an art collective with very little external restrictions.

- The orchid is actually a leitmotif of BIO28 Double Agent: Do You Speak Flower?. From Proust’s Cattleya between Swann and Odette, to Anna Hulačová’s talking orchids at the entrances and Brendel’s botanical models of Orchis Morio… Murmuring Orchids concluded Alexandra’s curatorial storytelling while still offering a new perspective on this particular plant. However, you cunningly hid the meaning outside your installation.

Prostorož: By focusing on the housing crisis, we managed to shed new light on the orchids as plants. We invited our friend and curator, Jana Stardelova, to write the introduction text, in which she highlighted a dimension of those plants that we hadn’t noticed before. Her text explores the duality of orchids, balancing between wildness and domestication, parasitism and symbiosis. Jana also positioned the orchids int the context of colonialism and ecofeminism, adding another layer to Murmuring Orchids. These dualities are subtly mirrored in the stories of women, murmured by the orchids in the installation.

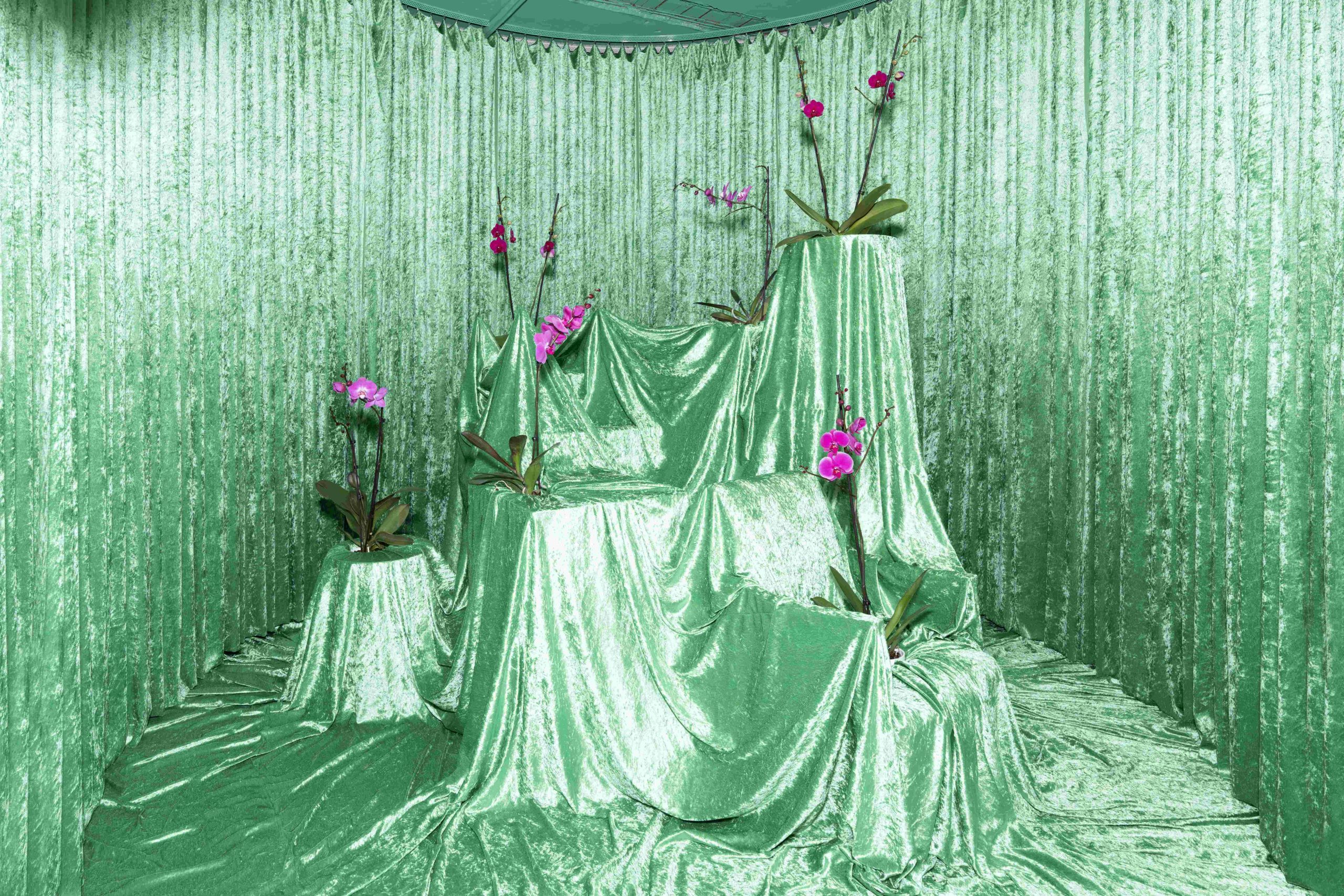

Installation ‘Murmuring Orchids’ at the Museum of Architecture and Design - MAO. Photo: Lucija Rosc

- When listening to the struggles and hardships shared by the women you interviewed, how do you decide which stories to highlight?

Prostorož: Firstly, there are no right or wrong struggles. Instead, we should focus on their causes. Half of our interviewees were non-Slovene women: an elderly woman who fled Palestine as a refugee, a programmer from Moscow unable to obtain Slovenian citizenship due to the war, and a young single mother from a Serbian town where everyone knew they were drinking contaminated water. Their past even deepens the difficulties they face in finding an apartment in Ljubljana. One of the stories was even shared by our colleague Naja. Although our studio offers fair working conditions and decent wages, Naja could no longer afford to pay new rents in Ljubljana. Due to the arrogance of landlords, she was forced to move five times in five years, with her rent increasing by a fifth each time.

- If you had to sum up your otherwise really multifaceted project into a single message, it would probably be raising awareness about the stories caused by Ljubljana’s housing crisis. What do you see as a systemic solution?

Prostorož: Despite the mistakes that have been made since Slovenia gained its independence, there have been many ideas and initiatives on how the housing crisis should be addressed. After all, we could look at neighbouring Vienna, which is already demonstrating what a solid housing policy provides for young people, migrants, people who are just arriving in the city. We need bolder political measures and new laws that would be able to offer the same in Slovenia. The proposed second property tax is certainly not a sufficient answer for the pressing crisis.

- Could you pinpoint the bare minimum that each of us can provide to make the situation even a little bit better? What do you wish to provoke in visitors?

Prostorož: We notice that society nowadays is very quick to blame the individual for the situation they found themselves in. With the housing crisis, this is even more evident. One of the interviewees ran away from home due to domestic violence and then fell pregnant with a partner she didn’t know well. Now, as a young single mother, she’s finding it increasingly difficult to find an apartment to rent in Ljubljana. It would have been very easy to conclude that the pregnancy was her choice and therefore her fault. In this way the blame can be very quickly individualised, even though the housing shortage is a systemic issue. When you’re listening to the stories of our orchids, it’s clear that it’s impossible that women with such different backgrounds can all be blamed for their own situation. This is truly the strongest message of our project.

Prostorož chose MAO's project space for their installation. The space itself highlights a duality: the bare walls of the museum's unrenovated section on one side, and the soft velvet of Murmuring Orchids on the other. Photo by Urban Cerjak for MAO.

- What are the plans for the echoes of Murmuring Orchids in the future?

Prostorož: Right now, they’re waiting for decomposition, so to speak. At Prostorož, we’re always thinking of ways to reuse and recycle the materials and elements that we use. The orchids echoed beyond the exhibition thanks to protest actions by Stanovanjski blok initiative. We’re not sure if they plan to play the recordings again, but we’re glad that they were heard outside of MAO as well. Our collaboration with Polonca Lovšin enabled us to inspire a performance by the undergraduate students of Visual Arts and Design from the University of Primorska. Their performance will conclude the installation at the guided tour of Double Agent at MAO on Sunday, 30th March 2025, at 11 AM. Lastly, the green velvet surrounding the orchids will be travelling to Milan Design Week, where the Centre for Creativity is hosting and organising the Material bar from 7th-13th of April 2025. There, we will create a new installation: we will create soft giant poufs at villa Alcova and invite like-minded Italian collectives to meet us there

Interview by Nuša Zupanc Pavlič, editor of BIO, with the Prostorož team.

*******

Production platform Movement for Public Speech* is mentored by Polonca Lovšin. Polonca Lovšin is an architect and artist based in Ljubljana. In her work, she focuses on self-organized initiatives and alternative ways of living and working related to architecture, urban planning, and environmental issues. She is exhibiting her work internationally in solo and group exhibitions and has been awarded numerous grants, awards and residencies.

Movement for Public Speech is a sculpture in public space, a monument to public speaking and participation. By definition, public speaking is the discussion of people in a public space about important issues in society. This project challenges the relationship between the audience and the speaker and portrays this relationship as interdependent. The speaker's speech can only be heard over the sound system if he is supported by the audience, who synchronously press, pull, or step on the manufactured devices. The foundation of this project is the collaboration of two different roles – those who move to support the speaker and the speakers themselves. The common goal of the "movement" is to visualize the interdependence of all involved, who support each other and build alliances – a community.

Today, in times of crises (economic, political, social, and environmental), it is essential to speak in public about the issues of human society, which are often overlooked, forgotten, or insufficiently present in public discourse. It is equally important that we listen to them and hear them. The project, which is playful and serious at the same time, demonstrates the importance of cooperation and interdependence to achieve a common goal and thereby create a vision of a different society.

The Venus flytrap, a carnivorous plant that sets a trap to surprise and eat the fly, serves as the intellectual and design framework for the BIO28 edition of Movement for Public Speech. Are we humans caught in a trap of our own making? Maybe we can resolve the trap by supporting and listening to each other, creating friendships, building communities, and creating a vision of an entangled future.

*The Movement for Public Speech is an ongoing project by architect and artist Polonca Lovšin, which was first installed in 2015 on Liberty Square in Maribor as part of the Maribor Art Gallery’s art in public space program. Since then, it has been performed six times in different cities (Maribor, Kočevje, Ljubljana, Feldbach (Austria), Strasbourg (France)), activating different audiences through collective action and building new communities.

Don't Teach a Flower How to Bloom

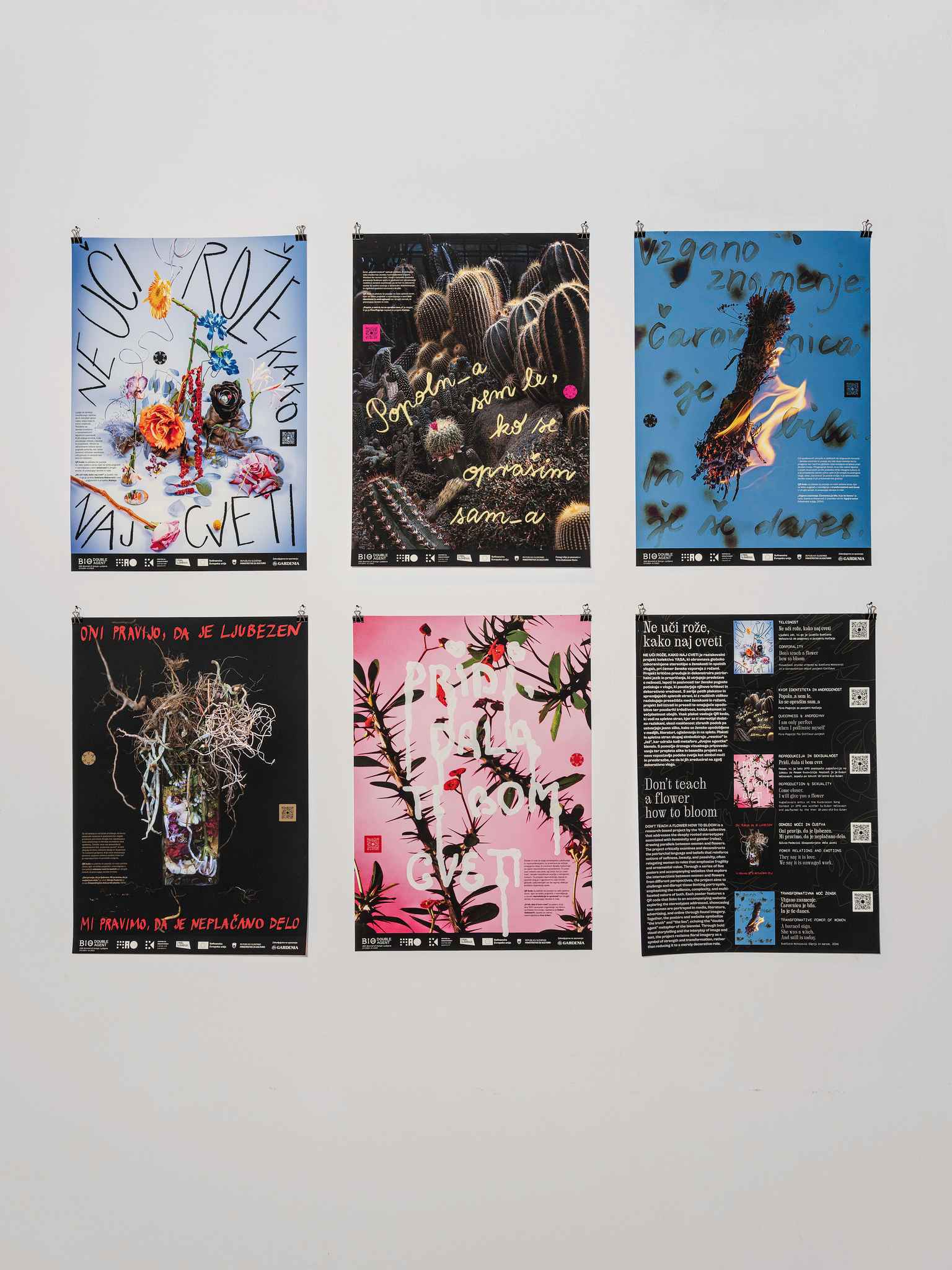

The YASA collective consists of visual artist Sara Bezovšek, visual artist and photographer Asiana Jurca Avci, journalist and curator Dora Trček and graphic designer Gaja Vičič. Although close friends, they joined forces professionally for the BIO28 production platform titled Cattleya and developed a project Don't Teach a Flower How to Bloom together with mentors Michelle Phillips (Studio Yukiko) and Grashina Gabelmann (Flaneur Magazine). The name of the production platform, Cattleya, derives from an orchid often nicknamed the queen of orchids, which is a leitmotif of the BIO28 Double Agent: Do You Speak Flower? exhibition. From Brendel’s Orchis morio botanical model, to Anna Hulačová’s masks, to an exhibition chapter titled Cattleya, which is actually Marcel Proust’s metaphor for an intercourse by his literary protagonists Swann and Odette in In Search of Lost Time. After exploring the too-often internalised patriarchal patterns that associate women with flowers, the YASA collective also studied Slovenian literature and folklore, and our habits, and chose the most traditional tool of visual communication - a series of posters - as their double agents. The posters offer a portal into the diverse underworld of the subject matter, where the content found in various media, in advertising and online forms a mosaic of views on how women are portrayed and understood in contemporary society.

- How did you start working together and what were your first impressions when reading through the BIO28 production platform brief for Cattleya?

Gaja Vičič: We formed a collective specifically for the Double Agent production platform, but actually we've been friends for years. When I saw the open call for Cattleya, I immediately sent it to Asiana, Sara and Dora, because we had often discussed the topic, and we were also very close artistically to the themes of the project. At that moment, I was in the middle of an important career transition myself, as I was moving from the field of graphic design into the field of floristry and starting to explore flower compositions. This open call combined many of my interests and came along just at the right time.

- How did your collaboration with BIO28 mentors Grashina Gabelmann and Michelle Phillips go?

Gaja Vičič: We had a great time working with Grashina and Michele, and we’re so happy with their contributions to Don’t Teach a Flower How to Bloom. I’ve been following and admiring both of their work for a while, and they’re very well known in Berlin, where I also live. Our collaboration was based on a relaxed, mutual dialogue, and they offered their support and guidance to us in just the right way so that we were able to better define our thoughts and ideas in the end. Our reflections and discussions with the mentors were really a valuable part of this project, but above all we are happy that, besides the collaboration, a friendship has formed between all of us.

Asiana Jurca Avci: I believe that we’d get along great, even if we’d meet without the help of Double Agent and the production platforms.

Urban poster project circulated for five months across various locations in Ljubljana. Photo: Asiana Jurca Avci, Tadej Kreft

- Could you briefly recap the seven-month process of the project? Did you initially have other concepts and plans in mind that you thought were great, but then didn’t feel right? What was the process of finding the right design expression that suited each of you?

Asiana Jurca Avci: Of course, there were several concepts and ideas during our seven-month work process. Firstly, we dived into floriography and herbalism and were exploring several options when it comes to a medium - from a booklet to a zine. The initial idea stemmed from tinctures and herbal mixtures used as alternative remedies to alleviate symptoms of PMS, depression, period cramps, anxiety, and various other mental and physical challenges affecting modern women. However, we soon realised that this approach would push us away from the core purpose of our platform. It risked reinforcing the traditional portrayal of women as caregivers and nurturers, an image to which women are still too often reduced. Alongside the fact that this is an omnipresent narrative, making it harder to offer something fresh, we then focused on a number of themes that we ourselves struggle with and wanted to research and address in depth, while simultaneously broadening our thinking and focusing on tangible sub-themes.

Sara Bezovšek: Each of us has a unique set of skills, and we successfully merged them in the final result. Asiana contributed photography, Gaja handled graphic design, I developed the website, and Dora wrote the texts. While our respective fields of work and research served as the foundation for our contributions to sub-themes, it was only natural that, throughout the project, we all played a role in shaping every aspect of the final outcome.

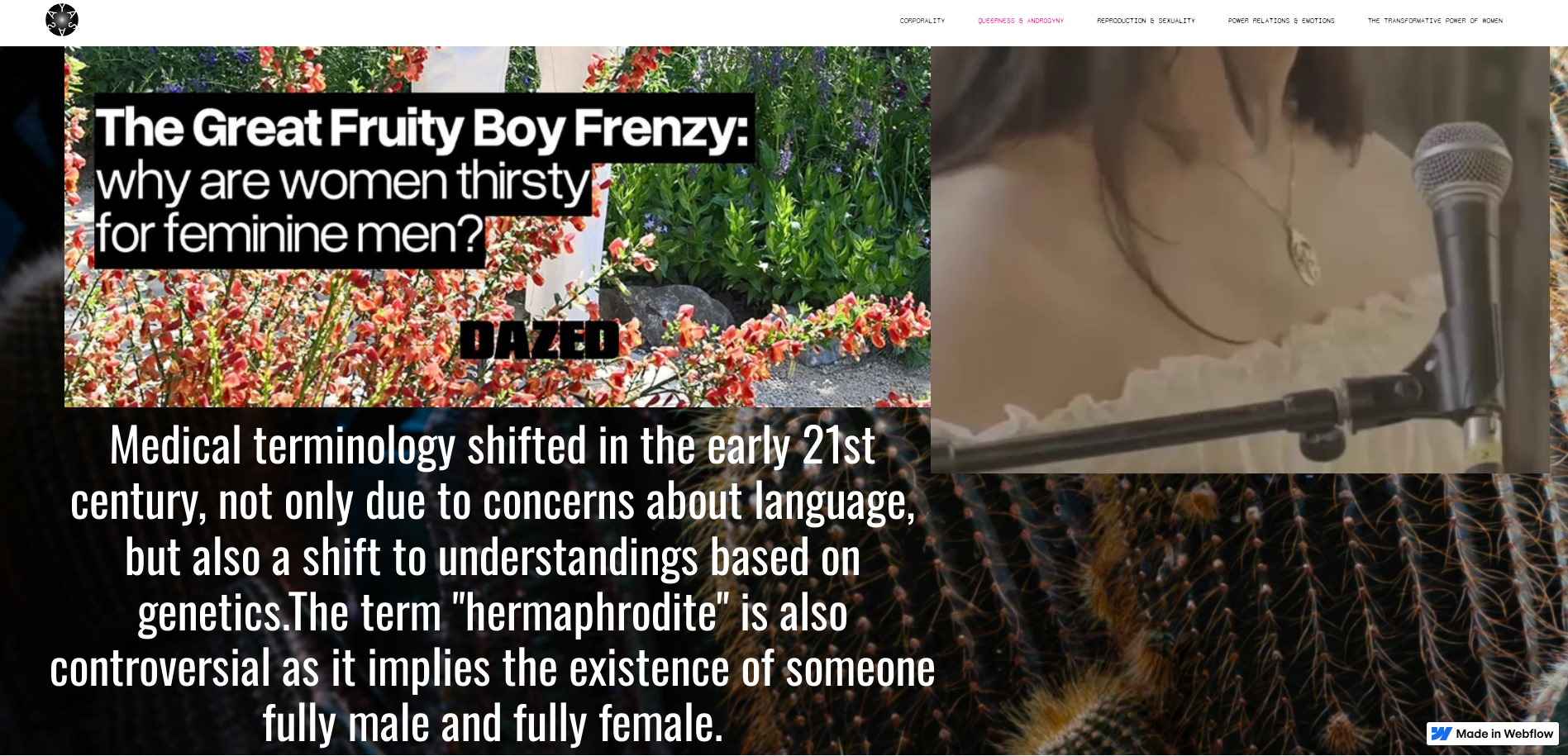

- In your case, the posters serve as double agents and an entryway into researching womanhood. On your website you developed a cross-sectional study with several sub-themes: Queerness & Androgyny, Reproduction & Sexuality, Power Relations & Emotions and Transformative Power of Women. How has your perception of these themes evolved from the start of your research to the completion of the project?

Gaja Vičič: We quickly realised that posters as mediums for our work just wouldn’t be able to summarise the wideness of the topics we researched. It took us several months to gather materials for each of the sub-themes, and we purposely decided to comb through different types of outlets: social media, marketing campaigns, websites... It was a really long process and, alongside that, there was a lot of self-reflection and dismantling of our internalised thinking patterns going on, too. Our perspectives, which of course differed from one another, also contributed to thinking about and highlighting these themes.

Asiana Jurca Avci: A poster is actually one of the oldest tools of visual communication and graphic design, that coincidentally addresses us everywhere we go. And if you look closely at the number of posters and billboards addressing women specifically, you’d be unpleasantly surprised: often, the campaigns on these posters are actually commodifying women. The posters we developed are, in fact, double agents as you say, and the hidden underworld of deeper themes is revealed only to those who show enough interest in the Don't Teach a Flower How to Bloom project. This infinite underworld offers insight into a contemporary hidden world of information. Our slogans and images on the posters also allude to stereotypes about women and the symbolic connections between women and flowers. We aimed to make the website a realistic reflection of womanhood today, presenting both the positive and negative aspects.

- If we do some shadow-work, which internalised thinking pattern that significantly impacts how we perceive the world would you dismantle first?

Asiana Jurca Avci: It’s really hard to pick just one, because they’re all interconnected and actually codependent.

Gaja Vičič: I would start by deconstructing the notion that the world is binary. Our sub-theme or chapter, Queerness & Androgyny, seeks to embrace the broadest possible perception of the world and emphasises that reality is far from just black and white. Sexualities and genders exist on a spectrum, and applying this perspective to how we view the world can lead to a more progressive way of thinking. Personally, I believe the queer chapter encapsulates some of the most crucial steps we can take to move forward towards a more equitable future, as it actively dismantles the restrictive binary mindset.

Sara Bezovšek: In our society, queerness is still viewed as something strange and foreign, even though it can be present in heteronormative relationships and in the various ways of perception of womanhood and femininity.

Asiana Jurca Avci: That’s right: through a queer identity, you can break down the restrictive perception of what a woman must be and instead shift your perspective toward exploring the broader possibilities of what a person can be.

Website Don’t Teach a Flower How to Bloom.

- BIO refuses to be ‘just another design show’. It’s a living organism that wishes to be provocative and offer a starting point for self-reflection through the spectrum of design, as well as inviting us to reevaluate the ways we think and act collectively. How do you view the role of a design biennial today?

Sara Bezovšek: I am participating in the BIO production platforms for the second year in a row, and I think the concept of biennial that includes production platforms is very well thought through. Perhaps it would make sense to optimise the work processes and improve the communication between mentors and participants, so that even deeper relationships can be developed, as has happened with our team and Grashina and Michelle. I also think the concept of production platforms is great, because in our professional environments there is almost no such approach. BIO offers valuable time to develop a viable concept and, most importantly, a process which allows you to create a really meaningful and complex project.

Asiana Jurca Avci: It would be interesting to see a BIO exhibition that includes production platform projects as part of the curatorial approach, exhibited alongside other projects and exhibits. I’m interested to see how the exhibition would change if a curator would develop a curatorial story together with the production platforms projects, and not separately. We had a discussion with Alexandra Midal, and we managed to find a way to exhibit Don't Teach a Flower How to Bloom in the main exhibition area due to the fact that other exhibition spaces dedicated to the production platform projects were too small for our contribution. I actually think that the rest of the production platform projects in other exhibition spaces could be weaved into Alexandra’s curatorial story as well.

- In developing the project, you have also managed to invite the field of design into a dialogue with other creative disciplines.

Asiana Jurca Avci: The basis for the process of developing Don’t Teach a Flower How to Bloom really stemmed from a multidisciplinary approach. Right at the beginning of the project, we met with the author Svetlana Makarovič, as we knew from the beginning that her work and her presence in our culture personifies what we’re trying to encompass with this project. During our conversation, she mentioned the phrase ‘Don’t Teach a Flower How to Bloom’ and we knew right away that this was our title. For the Queer identity poster, we were searching intensively for a Slovenian reference and published a small open call for all queer writers interested in contributing a slogan for one of our posters. This open call led us to Pino Pograjc, a young poet and a literary critic. After briefing him on the project and what we were aiming for, he translated our vision into a couple of meaningful slogans. Pino’s phrase perfectly captures a key starting point of our research - the fact that most of the flowering plants photographed for our project are dioecious, a term botanists refer to as perfect flowers. His slogan 'I am only perfect when I pollinate myself' perfectly summed up the idea of self-sufficiency, emphasising that only we truly understand the depths of our own needs, and no one else can fulfil them as completely as we can.

Gaja Vičič: Pino Pograjc contributed another great quote that we didn't end up using: Let me bloom where you pricked me. We felt it was perhaps too focused on the pain, and hinted at the intense hostility that queer people still experience today. We also contacted Karsten Fatur, an ethnobotanist and researcher at the University of Vermont, and he shared with us his study Queer Ethnobotany on the impact of queer theory on botany. This opened up a scientific dimension, which was essential and very interesting for the development of our project. Two other professionals played an important role in defining the five themes presented on the website. Dr Renata Šribar, an anthropologist and sociologist, reviewed our research and helped us to extract the essential themes and articulate them more clearly, and Dr Živa Fišer contributed her knowledge on the link between folklore and plants, which further enriched the project.

Round table with mentors Grashina Gabelmann and Michelle Phillips during the opening days of Don’t Teach a Flower How to Bloom. Photo: Urban Cerjak

- Can we expect a new chapter or a new series of posters in the future?

Asiana Jurca Avci: Certainly, we would like to continue this project. During BIO28, we demonstrated how toxic it is to draw parallels between women and flowers, but in the future we’re aiming to expand our concept to include other struggles that we, as women, collectively face in this world every day.

Sara Bezovšek: We still have a lot of material saved that we didn’t manage to include, and we are also exchanging different starting points or concepts that would ensure the longevity of this project even after BIO28. If we, at some point, decide to continue expanding Don’t Teach a Flower How to Bloom, we have quite a lot of content already prepared. In a way, the project is still alive because these themes are so present and we are still exploring them.

Asiana Jurca Avci: But at some point we had to decide where to draw the line and stop compiling themes, so that we offered a coherent overview of not only the themes but also our work at Double Agent. We also pondered the idea of expanding this project into a participatory one, so that the general public could contribute the chapters or societal issues that are burdening them to our online archive.

- How do you feel living in a world that continues to reduce women (and anyone who identifies as such) to a specific appearance, social roles, and so on? What kind of world would you like to see and coexist in?

Gaja Vičič: I believe that each of us in our collective exists within our own micro-ecosystems, which we have helped co-create. I’m noticing how women are capable of building more inclusive and caring communities, which is crucial for healthy coexistence in this world. Through our actions and firm stances, we’ve carved out a better position for ourselves and are actively working to deconstruct limiting internalised patterns of behaviour. I’d like to emphasise that our openness is far from the reality of the everyday world. I live in Berlin, where such openness is possible, but when I travel to a nearby town, it’s a completely different situation. I would appreciate it if some of the themes we developed through Don’t Teach a Flower How to Bloom were discussed more widely in mainstream media, so that the general public could begin to question the existing systems.

Sara Bezovšek: In general, I’m noticing significant changes in how women think nowadays. I’m from a very small alpine area, and even in such a traditional environment, I’m seeing progress as women no longer have to be just housewives. That’s promising, but when I focus on the larger political context, I’m not noticing much change, and the current situation doesn’t give me much hope either.

Asiana Jurca Avci: Even the situation in the USA is so dark that I could say that as humanity we are moving one step forward and then ten steps back.

Gaja Vičič: Progress is, unfortunately, not linear. It may even be in the form of a spiral.

YASA Collective printed 7000 posters for the Double Agents, that the visitors can take home. Photo: Lucija Rosc

- What was the reaction of visitors to your project? For the duration of BIO28, your posters were circulating through various locations in Ljubljana, reaching out to the widest possible audience.

Asiana Jurca Avci: The overall response was positive, especially among women, who resonated with the themes almost immediately. It meant a lot to them that we took the time to compile and address the struggles and challenges they face daily. Our colleagues also really appreciated the project. What I found particularly interesting was my younger brother’s reaction. He isn’t as active on social media as one might expect from someone his age. He mentioned that browsing through our website and themes made him feel very uncomfortable, and that the overwhelming amount of negative perceptions of women was truly unsettling.

Sara Bezovšek: I noticed comments on our socials stating that nobody has hurt us and that we don’t even need feminism, as we’re all equal after all. Some comments were also pointing out that our collective is playing victims.

Asiana Jurca Avci: Nobody in this project is pointing fingers at anybody, we’re focusing on the fact that each and every one of us is responsible for making our collective situation better. Sometimes it’s even enough if we call out our peers.

If you had to summarise, what would be the main message of your project, or what type of thinking do you want to provoke in visitors to Double Agent?

Jurca Avci: That it’s incredibly complex to be a woman - or as a very well-known quote says: Girlhood is a spectrum.

Interview by Nuša Zupanc Pavlič, Editor of BIO.

******

Cattleya is a production platform co-mentored by Michelle Phillips (Studio Yukiko) and Grashina Gabelmann (Flaneur Magazine). Studio Yukiko is a Berlin-based creative agency specializing in creative direction, art direction, brand strategy, concept generation and graphic design for commercial and cultural clients alike. The studio is producing award-winning work, unearthing narratives, telling stories of local communities worldwide, and immersing themselves in the trends of internet and youth culture. Grashina Gabelmann is a founding member and editor-in-chief of the site specific, collaborative, and multi-disciplinary project called Flaneur Magazine. She works as a writer and translator. Her creative practices also involve listening as an act of care, giving political/creative workshops to kids, teenagers, and the elderly, and collecting stories in different communities.

The production platform Cattleya invites you to deconstruct the androcentric correlation of the female-as-flower. The name of this project is a glimpse into Marcel Proust's famous concept of cattleya (referring both to “making love” as well as the Cattleya orchid flower) from his opera In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower. The participants will reinterpret the mundane patriarchal idioms associating women to flowers by examining the rich connections between language and image that are pervasive in Slovene poetry, literature, the arts, advertising, and elsewhere as well. Therefore, it will question, criticize, and reformulate these relationships into a series of provocative and bold visual productions. Through zines, posters, and other manifestations of graphic design, the participants will focus on idiomatic expressions related to the comparison between women and flowers, thus visually exploring the cultural significance of these expressions.